What Luther's Trip to Saxony Teaches Us About Connecting Church and Home

My grandparents once had a wall of pictures in the long hallway at the top of the stairs in their home. I can remember my mom and aunts standing around the pictures after a new cousin was born, talking about how much the new addition favored one older relative or another. These days it seems like everyone is tracing their ancestry and genetic history. Discovering where we’ve come from helps us to understand something about ourselves.

That’s one of the reasons I love Martin Luther. He’s like a bombastic German uncle who has helped me to understand both the centrality of the gospel and the Bible’s two-fold strategy for family discipleship.

Beginning with a Focus on the Family

Luther’s plan for reaching the next generation began with a focus on the family. He was passionate about parents teaching their children. During the Middle Ages, professional clergy and church institutions such as schools and monasteries had taken pride of place in the role of passing down the faith. But with the dawn of the Reformation, church leaders called for a return to family discipleship, instructing parents, and especially fathers, to take an active role in teaching their children the faith.

Luther led the way. When giving his lectures on the book of Genesis, the reformer famously compared the Christian home to a school and a church:

Abraham had in his tent a house of God and a church, just as today any godly and pious head of a household instructs his children . . . in godliness. Therefore, such a house is actually a school and a church, and the head of the household is a bishop and priest in his house.

Luther moved the church from a culture of clericalism to a culture where every believer’s work mattered. The Wittenberg pastor believed that ordinary labors of life—everything from laboring at a trade to changing a baby’s diapers—are charged with meaning. He was convinced that God is always at work in our labors at home, no matter how ordinary they are, and he was also confident in the gospel’s power to move people’s hearts toward God. He believed that gospel preaching would move fathers to become disciple-makers within their homes and move in children to cultivate a love for God’s Word and his church.

Discovering How the Family Needs the Church

While Luther’s convictions about gospel-driven family discipleship never waivered, his experience visiting the churches of rural Saxony in the late 1520s seems to have convinced him of the need for some institutional safeguards as well. After the visits, Luther wrote the following with his typical fervor:

Good God, what wretchedness I beheld! The common people, especially those who live in the country, have no knowledge whatever of Christian teaching, and unfortunately many pastors are quite incompetent and unfitted for teaching. Although the people are supposed to be Christian, are baptized, and receive the holy sacrament, they do not know the Lord’s Prayer, the Creed, or the Ten Commandments, they live as if they were pigs and irrational beasts.

After seeing such depressing conditions, Luther prepared a catechism that could be taught both in homes (in German) and in church-sponsored schools (in Latin). He became convinced that parents couldn’t train up their children alone. They needed support from the church community.

Reaching Youth Culture While Leaving Mom and Dad Behind

In many ways, the story of contemporary family ministry mirrors Luther’s journey.

In 1844, the Young Men’s Christian Association (the YMCA) was founded in London to improve the lives of young working men; soon, churches followed this model by creating their own societies to reach young people—an early precursor to contemporary youth ministry. With the growing youth culture of the 1940s and ’50s, Christian leaders created organizations and ministries that sought to reach teenage culture for Christ. Parachurch ministries such as Young Life (1941) and Youth for Christ (1944) were quickly followed by age-directed youth ministry programs in local churches.

“Luther moved the church from a culture of clericalism to one where every believer’s work mattered. He believed ordinary labors of life—everything from laboring at a trade to changing a baby’s diapers—are charged with meaning.”

By the 1970s, 80s, and 90s, nearly most local churches had youth ministers who saw youth culture as their mission field. They set up drum sets, used lights and video, and played crazy Nickelodeon-style Double Dare games as a way of becoming “all things to all people that by all means [they] might save some” (1 Cor. 9:22).

One disadvantage of this programmatic youth ministry model was a growing sense among some parents that they themselves would never be able to reach their children. They needed younger, cooler youth leaders who were, one might say, “in touch with kids today.” During the Reformation, Luther had fought against the clergy-laity divide within the Roman Catholic church. But less than five hundred years later, many parents assumed the responsibility for evangelizing and training their children was best left with professionals. Here’s how Timothy Paul Jones described this mentality in his book Family Ministry Field Guide:

"School teachers are perceived as the persons responsible to grow the children’s minds, coaches are employed to train children’s bodies, and specialized ministers at church ought to develop their souls."

Connecting Church and Home

Thankfully, just as it did during the Reformation, the church has once again responded to an overemphasis on overly institutional ministry with a rediscovery of the Bible’s two-fold emphasis. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, a group of family ministry leaders formed what has come to be known as the family ministry movement. These leaders have proposed a number of creative alternatives to programmatic youth and children’s ministry that have put a stronger emphasis upon both church and home.

One key passage for the family ministry movement is Psalm 78:

[Things] that we have heard and known,

that our fathers have told us.

We will not hide them from their children,

but tell to the coming generation

the glorious deeds of the Lord, and his might,

and the wonders that he has done.He established a testimony in Jacob

and appointed a law in Israel,

which he commanded our fathers

to teach to their children,

that the next generation might know them,

the children yet unborn,

and arise and tell them to their children,

so that they should set their hope in God

and not forget the works of God,

but keep his commandments. (vv. 3–7)

This psalm reminds us how God, throughout Israel’s history, had the generations in mind. God wanted Israel’s children to remember what he’d done to rescue and save. He wanted them to remember his laws and commands. He wanted the kids to hope and trust in him. And God gave the responsibility for training kids in the faith to two distinct groups: to Israelite parents and to their covenant community.

God commanded “[Israel’s] fathers to teach their children” (Ps. 78:5). No one has more potential to influence a child’s spiritual direction than their parents. No Sunday children’s ministry will come close to mom or dad’s level of influence. Family ministry leader Reggie Joiner once compared the number of hours an average parent spends with their child to the number his church ministry team spent with the kids in their care:

At best, with those who attended our church consistently, we would only have about forty hours in a given year to influence a child. . . . The same fourth-grader who would spend nearly four hundred hours playing video games and studying math would spend forty hours in our environments with our leaders and teachers. That same day we calculated another number that shocked us: the amount of time the average parent had to spend with their children. It was three thousand hours in a single year.

Joiner’s 3,000/40 ratio is stunning. Family discipleship will happen in planned moments when parents pull out a Bible storybook, and it will happen in unplanned moments when a child is heartbroken, and her parents give comfort. It’s in living rooms and cars, at bedsides and the breakfast table when many kids will hear and see their most consistent presentation of the gospel.

But training the next generation isn’t limited to homes. God’s command for parents to teach their kids was given in the context of a community (“in Jacob . . . in Israel,” v. 5). Christian parents won’t fulfill their responsibility to be generational disciple-makers unless fellow believers support them. Here are a few reasons why church ministry to children and students is necessary that I’ve adapted from Steve Wright and Chris Graves:

To surround young people with godly adults who can provide love and care, truth they can build their lives on, and a model to follow (1 Cor. 11:1; 1 Pet. 5:2).

To reinforce a biblical view of the world. A child will sometimes listen to a children’s or youth ministry volunteer even though they’ve consistently heard the same truth from their parent (2 Tim. 4:2).

Because the family hasn’t been given the keys to the kingdom, the church has. Therefore, the church is needed to affirm the salvation of children, and it’s the ultimate spiritual accountability for the family (Matt. 16:19).

To be a neutral third party when there is a major family conflict, serving as an impartial advisor between parents and kids (2 Cor. 5:18).

To connect believing young people with other Christians, who support, encourage, and keep them accountable (Heb. 10:25).

To provide opportunities for young people to use their gifts to serve (1 Cor. 12).

Because the church fights for truth and sound doctrine. It protects families from being drawn away by false teaching (1 Tim. 3:15).

Because spiritual growth generally happens within the context of community (Eph. 4:11–16).

If kids growing up in Christian homes need the larger church family, how much more is the church needed to reach out and model the gospel for children who do not have Christian parents (Matt. 19:14; 28:19–20)? The Bible is clear. As Luther began to emphasize after his journey, children and students benefit from the combined influences of godly parents and the discipleship ministries of their local church.

Editors Note: This article originally appeared on Phoenix Seminary’s website.

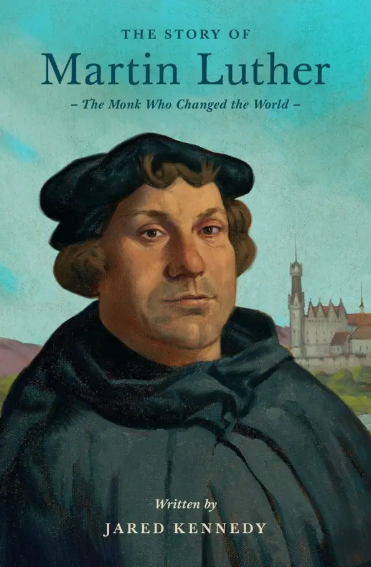

Check out The Story of Martin Luther: The Monk Who Changed the World by Jared Kennedy. This short and lively biography takes middle-grade readers on an exciting journey through Luther’s life, highlighting how his writings transformed the church and eventually the world. The Story of Martin Luther emphasizes the importance of Scripture and the fundamental doctrine the young monk discovered in Paul’s letters. Featuring illustrations, maps, timelines, bonus sidebars, and study questions, this book will engage kids ages 8–13 in the drama of history, showing how God worked in the past through people just like them.